Director Profile: David Lean

Although often associated in the public imagination with his later widescreen epics, the work of film director David Lean spanned numerous genres, from war films and domestic dramas to comedy, romance and literary adaptations. Despite the acclaim his films have received, and the multiple awards they won, Lean has not always been a critical favourite and his career was not without controversy.

David Lean was born in Croydon in Surrey in 1908 into a strict Quaker family, and was forbidden from going to the cinema until he was 17 years old. After a brief spell working at his father's accountancy firm, he joined the film industry as a tea boy at Gaumont-British Studios in 1927. There he graduated to clapper boy, before moving into the editing room, first on newsreels and then on feature films. Lean became one of the leading British film editors of the late 1930s and early '40s and worked on around two dozen features, including Pygmalion (1938), and Powell and Pressburger's 49th Parallel (1941) and One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942).

Lean chose his directorial debut carefully, turning down opportunities to make low budget quota fillers, and eventually settling on an offer from the playwright Noël Coward to co-direct his war drama In Which We Serve (1942), in which Coward was also starring. Lean's early career would be marked by his association with Noël Coward, following In Which We Serve with three films based on Coward plays; This Happy Breed (1944), Blithe Spirit (1945) and Brief Encounter (1945). These three films were all produced by Cineguild, a company Lean formed with the producer Anthony Havelock-Allan and Ronald Neame, the cinematographer on Lean's first three films, and later a director in his own right.

After this run of Noël Coward adaptations, Lean and Cineguild turned their attentions to Charles Dickens, with two acclaimed films based on his novels Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948). These two films, together with Brief Encounter, cemented Lean's reputation as one of Britain's leading film makers of the time.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Lean entered a less critically and commercially successful phase of his career, making three films starring his third wife Ann Todd; the romantic drama The Passionate Friends (1949), the crime drama Madeleine (1950), based on a celebrated trial in 19th century Scotland, and The Sound Barrier (1952), a fictional story about test pilots attempting to fly faster than the speed of sound. With the release of the second of these, Madeleine in 1950, Cineguild had produced its last film, and Lean, Havelock-Allan and Neame all went their separate ways.

Neither The Passionate Friends or Madeleine were particularly successful, but The Sound Barrier restored Lean's commercial and critical reputation, and won the British Academy Awards for Best Film and Best British Film. Lean followed this with the comedy Hobson's Choice (1954), starring Charles Laughton, Brenda de Banzie and John Mills, which won the same award for Best British Film, as well as the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. Lean's next film was the romantic drama Summertime (1955), also known as Summer Madness, with Katharine Hepburn as a middle aged American tourist in Venice.

With 1957's The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lean began his run of epic films, combining critical praise with blockbuster commercial success. An ironic WWII adventure about British prisoners of war forced to build a railway bridge for the Japanese, The Bridge on the River Kwai was a box office smash and won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Lean followed this with the grandiose epic Lawrence of Arabia (1962), based on the life of the enigmatic British soldier and adventurer T.E. Lawrence, played in the film by Peter O'Toole. Usually seen as the best of his epic films, Lawrence of Arabia repeated the success of The Bridge on the River Kwai and won seven Academy Awards including Best Picture, and a second Best Director win for Lean.

The Russian Revolution drama Doctor Zhivago (1965) was another huge hit, at least with audiences, but his penultimate feature film, Ryan's Daughter (1970), drew the opprobrium of critics, who felt that Lean had gone overboard, giving the epic treatment to a relatively small story.

Lean was so stung by the criticism that he lost enthusiasm for more film projects and didn't make another feature film for 14 years, although he did attempt to find financing for a two-part film based on the 1789 mutiny on HMS Bounty.

|

| Peter O'Toole and Anthony Quinn in Lean's 1962 epic Lawrence of Arabia |

David Lean was born in Croydon in Surrey in 1908 into a strict Quaker family, and was forbidden from going to the cinema until he was 17 years old. After a brief spell working at his father's accountancy firm, he joined the film industry as a tea boy at Gaumont-British Studios in 1927. There he graduated to clapper boy, before moving into the editing room, first on newsreels and then on feature films. Lean became one of the leading British film editors of the late 1930s and early '40s and worked on around two dozen features, including Pygmalion (1938), and Powell and Pressburger's 49th Parallel (1941) and One of Our Aircraft is Missing (1942).

After this run of Noël Coward adaptations, Lean and Cineguild turned their attentions to Charles Dickens, with two acclaimed films based on his novels Great Expectations (1946) and Oliver Twist (1948). These two films, together with Brief Encounter, cemented Lean's reputation as one of Britain's leading film makers of the time.

|

| Celia Johnson and Trevor Howard in Brief Encounter (1945) |

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, Lean entered a less critically and commercially successful phase of his career, making three films starring his third wife Ann Todd; the romantic drama The Passionate Friends (1949), the crime drama Madeleine (1950), based on a celebrated trial in 19th century Scotland, and The Sound Barrier (1952), a fictional story about test pilots attempting to fly faster than the speed of sound. With the release of the second of these, Madeleine in 1950, Cineguild had produced its last film, and Lean, Havelock-Allan and Neame all went their separate ways.

Neither The Passionate Friends or Madeleine were particularly successful, but The Sound Barrier restored Lean's commercial and critical reputation, and won the British Academy Awards for Best Film and Best British Film. Lean followed this with the comedy Hobson's Choice (1954), starring Charles Laughton, Brenda de Banzie and John Mills, which won the same award for Best British Film, as well as the Golden Bear at the Berlin Film Festival. Lean's next film was the romantic drama Summertime (1955), also known as Summer Madness, with Katharine Hepburn as a middle aged American tourist in Venice.

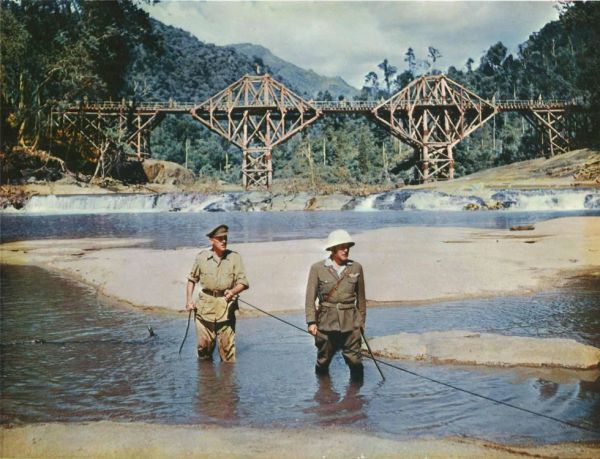

With 1957's The Bridge on the River Kwai, Lean began his run of epic films, combining critical praise with blockbuster commercial success. An ironic WWII adventure about British prisoners of war forced to build a railway bridge for the Japanese, The Bridge on the River Kwai was a box office smash and won seven Academy Awards, including Best Picture and Best Director.

Lean followed this with the grandiose epic Lawrence of Arabia (1962), based on the life of the enigmatic British soldier and adventurer T.E. Lawrence, played in the film by Peter O'Toole. Usually seen as the best of his epic films, Lawrence of Arabia repeated the success of The Bridge on the River Kwai and won seven Academy Awards including Best Picture, and a second Best Director win for Lean.

The Russian Revolution drama Doctor Zhivago (1965) was another huge hit, at least with audiences, but his penultimate feature film, Ryan's Daughter (1970), drew the opprobrium of critics, who felt that Lean had gone overboard, giving the epic treatment to a relatively small story.

|

| Alec Guinness and Sessue Hayakawa in The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957) |

Lean was so stung by the criticism that he lost enthusiasm for more film projects and didn't make another feature film for 14 years, although he did attempt to find financing for a two-part film based on the 1789 mutiny on HMS Bounty.

Eventually he returned to write, direct and edit one final film, A Passage to India in 1984, based on the novel by E. M. Forster. This time the critics acclaimed him again, and Lean's position as one of British cinema's greats was reaffirmed. He was knighted the same year and lived long enough to see his work championed by a new generation of film makers, with Lawrence of Arabia restored and re-released into cinemas in 1989. Lean was preparing his next film, an adaptation of Joseph Conrad's novel Nostromo, when he died in 1991 at the age of 83.

Like many directors, Lean had his regular collaborators, both in front of and behind the camera. As well as Noël Coward, Anthony Havelock-Allan and Ronald Neame, he also worked regularly with screenwriter Robert Bolt (3 films), cinematographers Guy Green (4 films), Jack Hildyard (4 films) and Freddie Young (3 films), designers John Bryan (4 films) and John Box (3 films), and composers Malcolm Arnold (3 films) and Maurice Jarre (4 films). Among the actors, Alec Guinness was the one most often called into service, appearing in 6 of Lean's films from 1946 to 1984, while John Mills appeared in 5, and Ann Todd and Celia Johnson in 3 films each.

Lean's association in the public imagination with outsized epics tends to obscure the fact that at the heart of his films there is often a very personal drama. This is as true of an earlier film like Brief Encounter or The Passionate Friends as it is of an epic, like Lawrence of Arabia or The Bridge on the River Kwai. Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai seems to be driven to build his bridge as much by a desire to matter, to produce a personal legacy, as to provide a project to boost his men's morale, or to have any impact on the war in which he is involved.

Lean's reputation for making epics can also obscure the fact that many of his protagonists are women, with at least six of Lean's sixteen features focusing on a female main character. In others, like Hobson's Choice, the storyline is driven by a woman, even when the nominal main character and star is a man. The theme of a woman caught between a dull marriage, or the possibility of one, and a more exciting affair with another man, is one that recurs in Lean's films, from Brief Encounter to Ryan's Daughter.

Lean sits in an odd position critically, a maker of highly acclaimed films, whose technical skills are undeniable, and yet as a director he has rarely been a critical favourite. Andrew Sarris sneered that Lean's films had “too little literary fat and too much visual Lean”, a line not dissimilar to the anonymous barb that “Inside every Lean film there is a fat film screaming to get out.” The antipathy was mutual, with Lean declaring that “I wouldn’t take the advice of a lot of the so-called critics on how to shoot a close-up of a pot of tea”.

Perhaps Lean's films were just too popular, or considered to be too tasteful and restrained, for critical tastes in the 1960s and 1970s. By the time of Ryan's Daughter, there was certainly a sense that Lean's literate, considered, carefully crafted style of film-making was falling out of fashion. But while critical fashions come and go, Lean's classical sensibility has a timeless quality that means it rarely appears dated, while his more fashionable contemporaries often do.

Maybe there was also a suspicion among critics that Lean was a talented technician, rather than an artist. But a closer examination of Lean's films shows a surprisingly personal film maker, often returning to the same or similar themes and visual motifs. His earlier films are marked by a keen eye and an ability to draw excellent performances from his actors, while his later epics display spectacular visuals on the grandest scale, without sacrificing the quality of the performances or losing sight of the human drama.

In 1999 the British Film Institute polled 1000 film and television industry personnel to compile a list of the top 100 British films of the 20th Century. David Lean was the most featured director on the final list, with seven films in the top 100 and a remarkable three films (Lawrence of Arabia, Brief Encounter and Great Expectations) in the top 10 alone. For audiences, and for his fellow film-makers, David Lean's position as one of the 20th century's greatest film directors has never been in any doubt.

David Lean Filmography

As director:

Major Barbara (1941) (some scenes; uncredited)

In Which We Serve (1942) (co-director)

This Happy Breed (1944)

Blithe Spirit (1945)

Brief Encounter (1945)

Great Expectations (1946)

Oliver Twist (1948)

The Passionate Friends (1949)

Madeleine (1950)

The Sound Barrier (1952)

Hobson's Choice (1954)

Summertime (Summer Madness) (1955)

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Doctor Zhivago (1965)

The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) (some scenes; uncredited)

Ryan's Daughter (1970)

Lost & Found: The Story of an Anchor (1978) (documentary short)

A Passage to India (1984)

See Also:

Madeleine (1950)

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

Like many directors, Lean had his regular collaborators, both in front of and behind the camera. As well as Noël Coward, Anthony Havelock-Allan and Ronald Neame, he also worked regularly with screenwriter Robert Bolt (3 films), cinematographers Guy Green (4 films), Jack Hildyard (4 films) and Freddie Young (3 films), designers John Bryan (4 films) and John Box (3 films), and composers Malcolm Arnold (3 films) and Maurice Jarre (4 films). Among the actors, Alec Guinness was the one most often called into service, appearing in 6 of Lean's films from 1946 to 1984, while John Mills appeared in 5, and Ann Todd and Celia Johnson in 3 films each.

Lean's association in the public imagination with outsized epics tends to obscure the fact that at the heart of his films there is often a very personal drama. This is as true of an earlier film like Brief Encounter or The Passionate Friends as it is of an epic, like Lawrence of Arabia or The Bridge on the River Kwai. Colonel Nicholson in The Bridge on the River Kwai seems to be driven to build his bridge as much by a desire to matter, to produce a personal legacy, as to provide a project to boost his men's morale, or to have any impact on the war in which he is involved.

Lean's reputation for making epics can also obscure the fact that many of his protagonists are women, with at least six of Lean's sixteen features focusing on a female main character. In others, like Hobson's Choice, the storyline is driven by a woman, even when the nominal main character and star is a man. The theme of a woman caught between a dull marriage, or the possibility of one, and a more exciting affair with another man, is one that recurs in Lean's films, from Brief Encounter to Ryan's Daughter.

|

| Omar Sharif and Julie Christie in Dr Zhivago (1965) |

Lean sits in an odd position critically, a maker of highly acclaimed films, whose technical skills are undeniable, and yet as a director he has rarely been a critical favourite. Andrew Sarris sneered that Lean's films had “too little literary fat and too much visual Lean”, a line not dissimilar to the anonymous barb that “Inside every Lean film there is a fat film screaming to get out.” The antipathy was mutual, with Lean declaring that “I wouldn’t take the advice of a lot of the so-called critics on how to shoot a close-up of a pot of tea”.

Perhaps Lean's films were just too popular, or considered to be too tasteful and restrained, for critical tastes in the 1960s and 1970s. By the time of Ryan's Daughter, there was certainly a sense that Lean's literate, considered, carefully crafted style of film-making was falling out of fashion. But while critical fashions come and go, Lean's classical sensibility has a timeless quality that means it rarely appears dated, while his more fashionable contemporaries often do.

Maybe there was also a suspicion among critics that Lean was a talented technician, rather than an artist. But a closer examination of Lean's films shows a surprisingly personal film maker, often returning to the same or similar themes and visual motifs. His earlier films are marked by a keen eye and an ability to draw excellent performances from his actors, while his later epics display spectacular visuals on the grandest scale, without sacrificing the quality of the performances or losing sight of the human drama.

In 1999 the British Film Institute polled 1000 film and television industry personnel to compile a list of the top 100 British films of the 20th Century. David Lean was the most featured director on the final list, with seven films in the top 100 and a remarkable three films (Lawrence of Arabia, Brief Encounter and Great Expectations) in the top 10 alone. For audiences, and for his fellow film-makers, David Lean's position as one of the 20th century's greatest film directors has never been in any doubt.

David Lean Filmography

As director:

Major Barbara (1941) (some scenes; uncredited)

In Which We Serve (1942) (co-director)

This Happy Breed (1944)

Blithe Spirit (1945)

Brief Encounter (1945)

Great Expectations (1946)

Oliver Twist (1948)

The Passionate Friends (1949)

Madeleine (1950)

The Sound Barrier (1952)

Hobson's Choice (1954)

Summertime (Summer Madness) (1955)

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

Lawrence of Arabia (1962)

Doctor Zhivago (1965)

The Greatest Story Ever Told (1965) (some scenes; uncredited)

Ryan's Daughter (1970)

Lost & Found: The Story of an Anchor (1978) (documentary short)

A Passage to India (1984)

Madeleine (1950)

The Bridge on the River Kwai (1957)

Excellent post on David Lean's career and his abilities as a director. I love how he was able to give us intimate character pieces set against epic backdrops, and also how he managed to find a perfect balance between the two.

ReplyDeleteSo many of his films are like works of visual art (Oliver Twist and Great Expectations being to prime examples of this)and you can spot his attention to even the smallest details in every shot. Even his weaker films have so much about them to recommend them and are well worth watching.

Thanks so much for taking part in this.

That's very true about the attention to detail, his films definitely repay repeat viewings. Even Madeleine, which is usually considered to be his weakest film, is fascinating, with lots of intriguing details and symbolism.

DeleteI enjoyed your article. What you said about the timeless quality of the Lean sensibility will ensure generations of rediscovery.

ReplyDeleteYes, I think so too.

DeleteGreat and informative article. I learnt a lot! I know more about his movies (without having seen so many either) than the man himself. David Lean surely was an artist and not just a technician!

ReplyDeleteDefinitely agree!

DeleteWhat a director! And what a great overview of the the man. He really had a sense of character and the emotional journey they undertake. I find Lean always added beautiful intimate touches to every scene despite his grand sense of mis-en-scene and sweeping shots. Thanks for a fantastic read!

ReplyDeleteThanks for your kind words. It's true that Lean's fastidiousness and attention to detail means that there's always something new to discover in his films, even the most familiar ones.

Delete