The Man in Grey (1943)

Genre Period drama / Romance

Country UK

Director Leslie Arliss

Screenplay Margaret Kennedy, Leslie Arliss; adaptation by Doreen Montgomery

Based on the novel by Lady Eleanor Smith

Running time 116 mins | Black & White

The Man in Grey is usually considered to be the first in Gainsborough Pictures' series of popular melodramas of the mid-1940s. The Gainsborough films won huge audiences during World War II and made stars of their leading actors, including Margaret Lockwood, James Mason, Phyllis Calvert, Stewart Granger, Patricia Roc, Jean Kent and Michael Rennie.

The film begins at a wartime auction, where an RAF pilot (Stewart Granger) is hoping to pick up a memento related to his family. The auction is a sale of items from the estate of the Rohan family, and he says that he is a distant relative. At the auction he meets an attractive woman (Phyllis Calvert) and discovers, a little belatedly, that she is a member of the Rohan family. The film then flashes back to the Regency era, and to these two characters' ancestors.

Clarissa Richmond (also played by Phyllis Calvert) is the most popular girl at the exclusive girls' school run by Miss Patchett (Martita Hunt). She isn't popular because she is beautiful and rich (although it doesn't hurt), but because she is kind and good-hearted.

When Hesther Shaw (Margaret Lockwood) arrives at the school to begin training as a teacher, she is prickly and hard to like. Hesther's awkwardness is largely due to her much more humble background than the others, her family having recently been made destitute. Miss Patchett has agreed to take her on only because she owes her mother a favour. But Clarissa is so kindly and welcoming that she befriends Hesther and the two girls become firm friends.

When the girls leave the school, Clarissa enters London society. There she attracts the attentions of Lord Rohan (James Mason), known as "the man in grey". Rohan is looking for a suitable wife to provide him with an heir for his family estate. But once they are married, Clarissa discovers that the cold Rohan has little interest in her and will spend most of his time away.

Soon, Clarissa runs into Hesther again, who is now an actress on the stage. She also meets, and gradually becomes attracted to, Hesther's co-star, the handsome Rokeby (Stewart Granger). This development is encouraged by Hesther, who seems to have her own plans.

Meanwhile, when Lord Rohan finally meets the more spirited Hesther, he finds her a much more agreeable match than his own unworldly wife. Will the ambitious Hesther really settle for being Rohan's mistress, or does she intend replacing Clarissa as his wife?

|

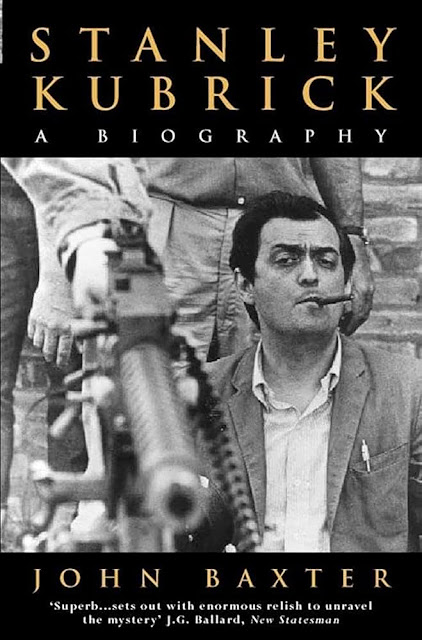

| Margaret Lockwood as Hesther Shaw with James Mason as Lord Rohan |

The melodramas made by Gainsborough in the 1940s became the studio's signature films. For wartime audiences, especially in Britain, their combination of lavish costumes and settings and relatively unrestrained passions made them an irresistible antidote to the rigours of World War II.

The Man in Grey was based on a novel by Lady Eleanor Smith. The film version was directed by Leslie Arliss and scripted by Arliss and Margaret Kennedy, with an adaptation credit for Doreen Montgomery. Leslie Arliss was a former journalist who had become a scenario editor at Gainsborough Pictures and directed a couple of films elsewhere, including The Night Has Eyes in 1942 with James Mason, before making The Man in Grey.

The Man in Grey is a reasonably typical example of the Gainsborough breed, with fancy costumes, handsome heroes, wholesome heroines, gypsy fortune-tellers, vampish love rivals and dastardly villains. On this film Leslie Arliss and his team, especially cinematographer Arthur Crabtree, designer Walter Murton and costume designer Elizabeth Haffenden, created the rich visual style associated with the Gainsborough melodramas.

Like Hammer, another British company making popular, but critically-reviled period fantasies, the studio's filmmakers made the most of relatively limited budgets. In the case of Gainsborough's films, these limitations were largely due to the strictures of filmmaking in Britain during wartime.

The plot of The Man in Grey hits the right points to move things along and keep it lively, but it's reasonably obvious that Kennedy and Arliss are shuffling their characters around at their convenience. When Hesther and Clarissa become firm friends at the school it's solely for reasons of plot mechanics, rather than due to any great bond they have forged or affinity they feel for one another.

|

| Phyllis Calvert as Clarissa with Margaret Lockwood as Hesther |

The film's dialogue also tends to spell out the characters' relationships a little too much, with everyone painstakingly telling each other exactly how they feel about things. The addition of a "modern" wartime framing narrative at the auction, which Granger and Calvert both attend in uniform, oddly dates the film much more than if it had been set entirely in the Regency era. It does, however, allow the makers to give the film a sad-happy double ending.

While Stewart Granger's Rokeby is penniless, initially employed as a travelling player and then as a fairground sideshow barker, in a film like this a grand inheritance surely can't be far away. And, sure enough, he is soon claiming that he is in fact the owner of an estate in the West Indies that was seized from his family by the French.

The film is a little ambiguous on the morality of making a fortune in this way - from an estate where the workers are presumably former slaves - with Rokeby initially telling Clarissa that he doesn't want to take the estate back by force from the poor, downtrodden workers who are now there, before later deciding that he should do exactly that.

The writers have also given Clarissa a black servant boy, Toby, as a companion. There obviously weren't many black child actors in Britain in 1943, so he is played by a white boy, Harry Scott, in blackface of varying degrees of plausibilty, depending on the scene. In his last appearance, the make up seems almost to have washed off, suggesting that having his character sit out in the rain wasn't the best idea. On this evidence, as a child, Harry Scott wasn't a very good actor anyway, and he is not up to the demands the part makes of him.

Fortunately, the film's quartet of stars make up for any shortcomings. Phyllis Calvert is winsome and appealing, Margaret Lockwood devious and scheming, Stewart Granger dashing and romantic and James Mason mean and moody. Of the four, Margaret Lockwood was the biggest name already, having starred in, among others, The Lady Vanishes (1938) for Alfred Hitchcock and The Stars Look Down (1939) and Night Train to Munich (1940) for Carol Reed.

Having Granger and Lockwood's characters Rokeby and Hesther playing opposite each other in a production of Shakespeare's Othello allows the script to provide them with a playful scene as the actors engage in a private conversation under their breath. Since neither likes the other very much, this descends into a covert argument, followed by Granger's Rokeby enjoying getting into character a little too much as he pretends to throttle Hesther.

As played by Lockwood, Hesther is a woman who intends to get what she wants, manipulating men, deceiving her friends and reinventing herself as and when required. She is impulsive - running off with a junior army officer early on in the film and then abandoning him - but determined.

|

| Phyllis Calvert's Clarissa looks pleased at the idea of marriage; Rohan (James Mason) seems less overjoyed |

Margaret Lockwood would continue to pursue her "bad girl" persona on screen, reaching its apotheosis in one of Gainsborough's most successful films, the 1945 highwaywoman saga The Wicked Lady. As a result of her work at the studio, Lockwood would be the biggest female star at the British box office in 1944, 1945 and 1946.

Among her co-stars in both The Wicked Lady and The Man in Grey was James Mason. Mason had been plugging away in films since the mid-1930s, but only reached stardom thanks to his Gainsborough work, where he was famously described as "the man you love to hate".

Dark and brooding, with that inimitable, silky, half-whispered voice, Mason could inflame passions and suggest unmentionable desires in a way that few contemporary British film stars could. Polls carried out at the time would show that Mason and Lockwood, and the less sympathetic characters they portrayed, were much more popular with audiences than the Gainsborough films' notional heroes and heroines.

The Man in Grey sees James Mason put in a star-making performance, after years of not quite breaking through into the big time. His character, Lord Rohan, comes from a family who take pride in their ominous motto of "Who dishonours us dies". We first meet him after he has just been injured killing a man in yet another duel, as he obviously takes that motto seriously. He is then seen arranging his dog's next brutal fight with another dog - dogfighting and killing people being just two of the pursuits that make him so loveable.

Although he is unsympathetic, Rohan isn't quite an out-and-out villain. He appears to love Hesther, but as he is now married, he won't leave his wife for her. Although, in fairness, it's mainly because he doesn't want any scandal attached to his family. He doesn't love Clarissa, but regards their marriage as a convenient transaction, from which she will derive wealth, comfort and status, and he will gain an heir.

In contrast, Stewart Granger's Rokeby has just enough bad boy swagger about him to be attractive, without ever going too far. He may hold up a stagecoach in one scene, but it's only with fake pistols, and he doesn't want any money, he just wants a lift. And in a nod to decorum, he only slaps the bad girl, not the good one, whereas Mason's Lord Rohan might well take a riding crop to either of them.

The two male leads would both work in Hollywood after Gainsborough made them stars. This included appearing opposite each other in MGM's 1952 remake of The Prisoner of Zenda. Both men often ploughed similar furrows in the US as they had at Gainsborough. Stewart Granger, whose real name was James Stewart - he changed it for obvious reasons - was usually the dashing hero (as in the 1950 remake of King Solomon's Mines or in 1952's Scaramouche) and James Mason the eloquent villain or quasi-villain (as in Disney's 20,000 Leagues under the Sea and Hitchcock's North by Northwest). Although Mason also essayed more demanding roles, including in Julius Caesar (1953) and A Star is Born (1954), and continued to work in British films, later becoming a respected character star.

|

| Calvert with Stewart Granger in the wartime framing sequence |

Phyllis Calvert continued to work for Gainsborough, where she was typecast as the virtuous heroine, but she did manage to invest the sometimes colourless characters with sympathy and life. The year after The Man in Grey she starred in three more films for the studio - Fanny by Gaslight, Madonna of the Seven Moons and Two Thousand Women - but her film career never prospered outside Gainsborough.

The Gainsborough melodramas are probably best understood as wartime fantasies of escapism, largely aimed at a female audience. Contemporary audiences could appreciate the grand houses, sumptuous settings and extravagant clothes in an era of restrictions, bombing and rationing. They could enjoy vicariously the bad behaviour, law-breaking or worse, often embodied by Lockwood's characters, while ostensibly championing the virtuous heroine (e.g. Calvert and, in later films, Patricia Roc). And they could fantasise about mean and brooding James Mason, while finding the handsome and more wholesome Stewart Granger to be an acceptable substitute. Not all of the films were period pieces, but the best known generally were and this was an important part of the appeal of the company's most successful films.

At the time, the critics were mostly sniffy and often keen to show themselves above such vulgar entertainments. The films' roots in Victorian stage melodrama and their deliberate appeal to women made them especially suspect to male critics at the time. But their escapist quality also separated them from the realist approach dominant in wartime British cinema. It wasn't until the 1980s that academics began to rehabilitate the Gainsborough films, particularly for their transgressive female characters and their social commentary.

Gainsborough Pictures had been in existence for around two decades by the time their melodramas appeared and the company had previously been most often associated with comedies, including several starring Will Hay. Although The Man in Grey set a profitable new direction for the studio, the cycle was relatively short-lived, petering out with Jassy in 1947.

The Gainsborough films did influence other contemporary British films, though, with rival companies, from Ealing Studios to David Lean's Cineguild, picking up the company's stars for their own versions. Stewart Granger featured in Blanche Fury (1947) with Valerie Hobson and Saraband for Dead Lovers (1948) with Joan Greenwood. James Mason, meanwhile, starred in rival melodrama The Seventh Veil in 1945, which was a big box office success, and Leslie Arliss directed Idol of Paris in 1948, which wasn't.

After The Man in Grey, Leslie Arliss made for Gainsborough the contemporary-set Love Story (1944), also starring Margaret Lockwood and Stewart Granger, and The Wicked Lady (1945), with Lockwood and James Mason. The latter film was the studio's biggest commercial success and, adjusted for inflation, is still one of the biggest ever hits at the British box office.

Cast

Margaret Lockwood - Hesther ShawPhyllis Calvert - Clarissa Richmond / Lady Rohan

James Mason - Lord Rohan

Stewart Granger - Rokeby

Harry Scott - Toby

Martita Hunt - Miss Patchett

Helen Haye - Lady Rohan

Beatrice Varley - Gipsy

Raymond Lovell - Prince Regent

Norah Swinburne - Mrs Fitzherbert

Uncredited:

Producer Edward Black Cinematography Arthur Crabtree Art Director Walter Murton Editor R. E. Dearing Music Cedric Mallabey Musical director Louis Levy Costume Designer Elizabeth Haffenden Make-up artist W. T. Partleton Period adviser C. H. Hartman Production manager Arthur Alcott In charge of production Maurice Ostrer

Production company Gainsborough Pictures

I thought Grey was good, but not great. Anyhow, James Mason is always a welcome addition to any movie. Love his voice! I thought he was particularly great in The Seventh Veil.

ReplyDeleteMason was always good. Even in his lesser films he was always a total pro. The Seventh Veil is similar to some of his Gainsborough roles, but it's an interesting one that I've been meaning to take another look at.

DeleteThis is beautifully written – my fave is "critically-reviled period fantasies" – and it's made me want to suss out this and other Gainsborough titles for this dreary afternoon.

ReplyDeleteThank you. Gainsborough's melodramas are definitely worth checking out as they can be a lot of fun.

Delete